REVIEWS

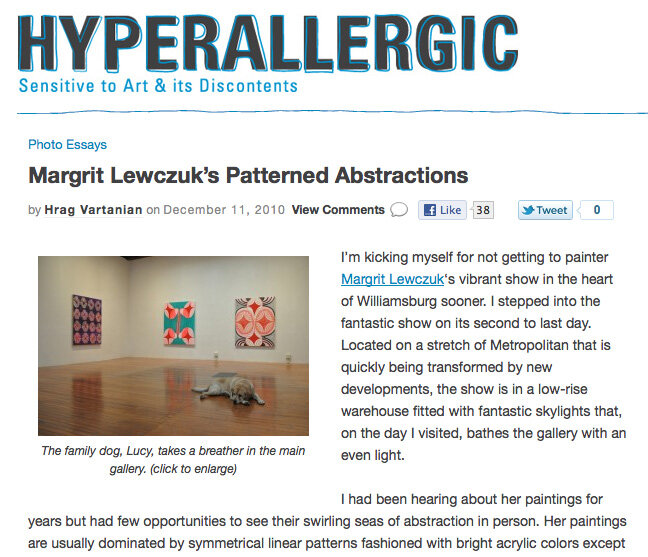

hyperallergic.com, review, December 2010 read the rest of the review and see the show…

MARGRIT LEWCZUK Me, We

By Tyler Akers

ON VIEW

The Gallery @ 1GAP

Richard Meier On Prospect Park

January 17 – April 23, 2015

New York

Painter Margrit Lewczuk’s career was marred in 1999 by a fire that destroyed the contents of her Chelsea studio. 16 years later, she has assembled a new oeuvre of vibrant paintings, drawings, and cut-outs while living and working in her Brooklyn home with her husband, fellow impassioned artist and professor Bill Jensen. The artist’s influences are not easily identifiable; in her work one might sense the organic symmetry of Ukrainian or Mexican folk art, the vibrating illusions of ’60s Op art or Islamic textiles, the expressively abstracted mathematics of Agnes Martin, the macro focus and whimsy of Hilma af Klint, or the playfully curved shapes and lively palettes of Henri Matisse or Yayoi Kusama. In devotion to the theme of her own transformation and renewal after disaster, her new work features symbols of rebirth such as eggs, angels, crosses, and the chrysalis. With these hopeful themes, she doesn’t mourn the past; she celebrates the potential of the present and future, affirming the power of long change, in gestation, incubation, and meditation.

Margrit Lewczuk, “Untitled,” 2009. Acrylic on linen. Courtesy of the artist.

Margrit Lewczuk, “Metamorphosis,” 2011. Acrylic on linen. Courtesy of the artist.

The paintings on view in Me, We are combinations of neon, jewel-tone, and neutral acrylics arranged in organic, symmetrical patterns charted over fluid grids, flat shapes with visible brushstrokes. Lewczuk applies paint in thick layers and rarely uses more than five or six colors. “Untitled” (2009), for example, is a giant red egg with luminous sky blue margins penetrated by four smaller white and pink eggs from the corners of the frame, forming the double image of a cross within the egg. Many of the other canvases also feature rounded shapes both at the center and blooming inward from the corners, establishing an amusing figure-ground shift of focus. A process of extended looking reveals the impact of this optical dance.

“Metamorphosis” (2011), a large abstract painting hung across from a conference table and chairs in the exhibition, centers on a golden yellow hourglass shape pinched between a pair of pea-green ovals, all surrounded by radiating concentric circles and shapes. The twin ovals appear to be on the edge of merging or at the end of separation, vibrating and shifting as if through the stages of cellular mitosis. Perhaps as a reference to Gregor Samsa’s tragic and terrifying fate in Franz Kafka’s tale, the green ovals of the painting become menacing, insect-like eyes, a reminder of the more grievous, alienating, and unrelenting aspects of change.

The title of Lewczuk’s show, Me, We, refers to a short poem delivered by boxer Muhammed Ali at a Harvard graduation address in 1975. Much like the exhibition, the words were meant as a simple statement of togetherness, a quick gesture toward intimacy. Fitting, as the venue for the show, the ground floor of a lavish apartment building designed by Richard Meier on Prospect Park, offers more in the way of close observations that come from living with a work of art than the average white box gallery. The space features a lobby and three small gallery lounges filled with TVs, couches, and cafe tables, all connected by a long narrow hallway. As the building is residential, the show can only be visited by appointment, which gives it an exclusivity that may seem contrary to its all-embracing title. But the cozy setting allows visitors to hide away with Lewczuk’s paintings, offering a space to sit and spend time, to look, to take a lunch break or a nap, and then look again, readjusted.

The two unisex bathrooms deliver perhaps the most intimate experience with Lewczuk’s work. In each, a mid-sized canvas painted with glow-in-the-dark acrylics creates a figure-ground reversal as the light is flipped on and off. In one painting, black squares form a wobbly grid over a neon orange and greenish-white background—until the overhead light is turned off to reveal the silhouette of a dancing figure glowing in luminous green. “Angel” (2014), a larger version of this painting, which hangs in the second gallery space, also boasts the trickery of this phosphorescent acrylic. Unfortunately, due to building policies, the light in the lobby and connected galleries must stay on continuously. Most of the work is visible from the sidewalk outside the building; it’s a shame the passerby doesn’t get to see the show glow with new imagery after sunset. Why worry though? Relaxing with Lewczuk’s work in this lounge setting enables the soothing details of her work to emerge and wash your cares away.

Contributor

Tyler Akers

Margrit Lewczuk: Being & Nothingness

http://artdealmagazine.blogspot.com/2015/01/margrit-lewzchuk-being-and-n...

Margrit Lewczuk, Angel, 2012, 60x48, acrylic on linen (courtesy of the artist)

Addison Parks writes about the work of Margrit Lewczuk. Lewczuk's show Me,We, curated by Suzy Spence is on view at The Gallery @1GAP, Brooklyn through April 23, 2015.

Parks writes: "Lewczuk paints monuments. To some being. To some Beingness. Like some extraterrestrial landing strip, like crop circles from space, with deafening sound, she reaches out. Encircling us. Embracing us. Hypnotizing us. Matisse as Svengali. Brancusi as painter. We find ourselves at her gate. Let go and she takes us in. The great mother. The Buddha. The unanswerable. The nothingness."

via:

Artdeal Magazine

Artdeal Magazine is a touchstone for artists; what it means to choose a life devoted to art, and how to survive and flourish as such. It provides sanctuary. This blog will do as intended; offer a running commentary, a little reminder, a yes for being an artist!

Saturday, January 17, 2015

MARGRIT LEWCZUK: Being and Nothingness and the Infinity Game

Margrit Lewczuk Untitled (2012) 60 x 48

There is an awe. Awesome. Transcendent painting that becomes all things! Nothing less will do. A kaleidoscope of Godhead! A microscope of cosmic eye blinking back at us. At once pleasure and pain, haunting and fun. Easter Island, Coney Island, the Island of Dr Moreau! The island of Lemnos. The third eye, the third world, around third base heading home, and back to the womb. A duet of pairs, a minuet of symmetry, a dizzying ballet of balance and centering and equilibrium.

Margrit Lewczuk, Connie’s Dream, (2006) Acrylic on linen, 60 x 48″

Green & Purple, (2008) Acrylic on linen, 60 x 48″

Margrit Lewczuk paints monuments. To some being. To some Beingness. Like some extraterrestrial landing strip, like crop circles from space, with deafening sound, she reaches out. Encircling us. Embracing us. Hypnotizing us. Matisse as Svengali. Brancusi as painter. We find ourselves at her gate. Let go and she takes us in. The great mother. The Buddha. The unanswerable. The nothingness.

Margrit Lewczuk Begin (2011) 60 x 48

Lewzcuk plays the infinity game. Yin Yang. Lemniscate. Möbius strip. Cassini's curve. Bernoulli's curve. Watt's curve. The devil's curve. The ouroboros. The aura. The oracle. The round sound(Om). A world within worlds. Archetypal. Algebraic. Alchemical. Ancient.

Margrit Lewczuk, Angel (2012) 60x48 Acrylic on Linen

Margrit Lewczuk, Journey (2011) 60x48 Acrylic on Linen

Cyclical. Cycladic. Cross cultural. Chrysalis. Cross hairs. Across time. The Egyptian Scarab. The Roman Millennium. The Latin Cross. The Lotus. The birth. The rebirth. The transformation. The transcendence. Space and time. The hour glass. The butterfly. The Omega.

Margrit Lewczuk Untitled 11 x 13 inches

Margrit Lewczuk is that butterfly. Her paintings are those butterflies. Her avatars. Flapping their wings before us. The smack down simplicity of it all. The eternal mystery of it all. The space odyssey of it all. The all. The one. The ME, WE.

Addison Parks

Spring Hill, 2015

Margrit Lewczuk Me,We, curated by Suzy Spence for The Gallery @1GAP

Opening Reception :Saturday January 17, 6 - 8PM

1 Grand Army Plaza, Brooklyn

Richard Meier On Prospect Park

The Gallery@1GAP

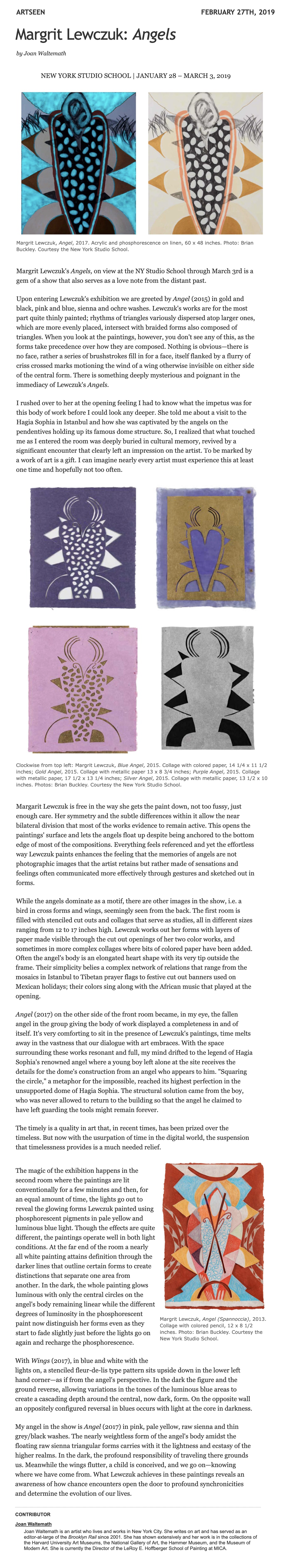

Margrit Lewczuk: Angels

Margrit Lewczuk, Angel, 2017, Acrylic on linen, 60 x 48 in., photograph by Brian Buckley.

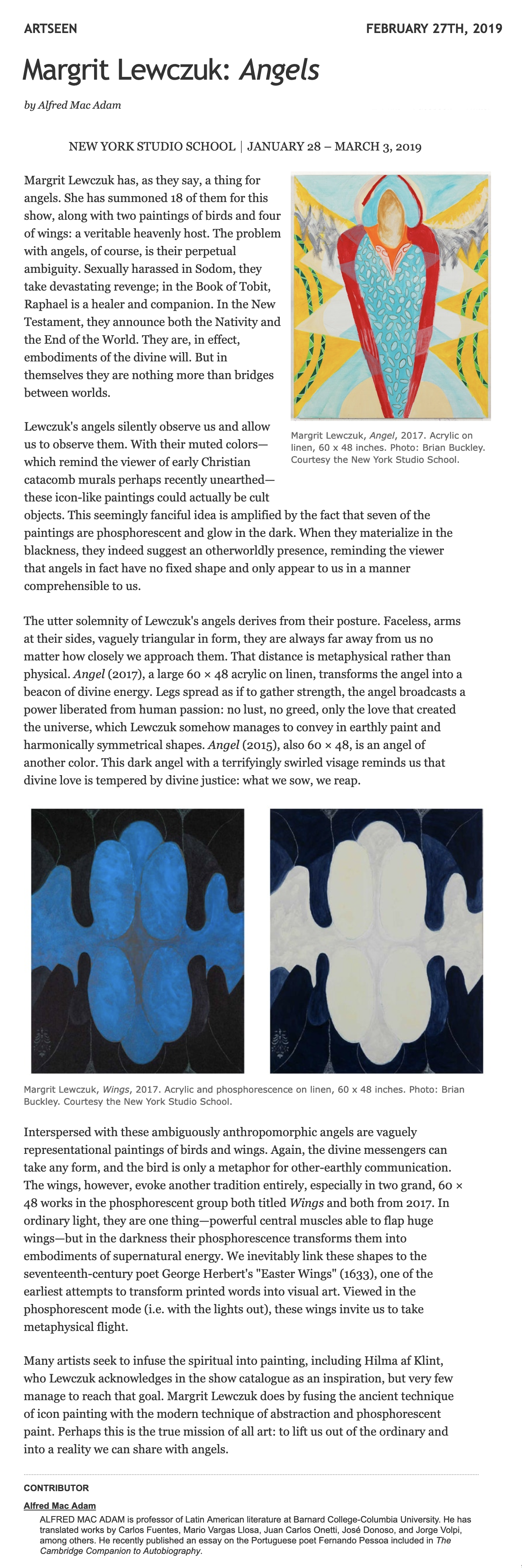

The New York Studio School presents Margrit Lewczuk: Angels, on view January 28 through March 3, 2019. Lewczuk has been exploring a nexus of iconic imagery that exudes the healing agency of painting–as well as its emanation of light–using forms sourced from both nature and abstraction. After a visit to the Hagia Sophia in Istanbul, Turkey, and seeing the un-identical Angel figures featured in the four pendentives, one in each corner, Lewczuk was inspired to initiate her own version of the Angel image.

In the Angel paintings, both sharp and soft shapes frame a tapered core, each almost symmetrical, but brought to the realm of humanity in the inexact mirroring. The exhibition features a series of large scale 60 x 48 inch paintings, and a group of small works on paper, painted in bold colors as well as phosphorescence. Half of the Gallery is curtained off, with the lights alternating on and off every few minutes, in order to activate the magic of the phosphorescent paint, and allow viewers to bask in a space only illuminated by the paintings’ own glow. A mysticism dominates the paintings’ aura, encompassing spiritual interpretations, as well as an otherworldly sensation. These works are for the believers and non-believers alike.

_________________________________________________________________

Here however, in this exhibition, we can see a form of the angelic — the “art” form— in which the artist’s image of the angel becomes the presence lost to (say) Protestantism, or Positivism. Margrit Lewczuk’s images are (I would say) larval angeliforms, both in the sense of cocoons, and in the sense of ghosts – i.e., they are both not-yet-born and “born again.” You might see such forms hovering over Egyptian mummy cases in the museum – messages that have been waiting for thousands of years to reach you.

-Peter Lamborn Wilson, Nov. 2018, excerpt from his foreword in the Exhibition Catalogue. Peter Lamborn Wilson is the Author of Angels published by Thames and Hudson, London.

CLICK TO VIEW INSTALL SHOTS

Press

TUESDAY, MAY 17, 2011

Schemas and Terrains: Margrit Lewczuk + Rockwell Kent

Maps, or signs, conflate landscape with diagram, transforming geography into hybrid schemas. Wikipedia defines shema: "The word schema comes from the Greek word "σχήμα" (skhēma), which means shape, or more generally, plan. Schema may refer to:Model (abstract), Diagram, or Schematic, a diagram that represents the elements of a system using abstract, graphic symbols." The distancing layer of stylization help us navigate unfamiliar space; visually, it presages digital screens. I think about schemas after seeing Margrit Lewczuk's exhibition, Drawing Into Paint. Her works re-interpret non-western sources as abstract systems similar to maps or signs. They alchemize graphite, gouache and paint into mysterious patterns that juggle allusions to figure and landscape while merging a map's reductive topologies with the colorful brevity of signage.

Click the header above to visit Lewczuk's website, and peruse the Brooklyn Rail interview to read about her experiences as a painter. Even better, head to Janet Kurnatowski in Greenpoint to see the paintings live! Check the gallery's website here: http://www.janetkurnatowskigallery.com/

Lewczuk's paintings are pure buoyancy, saturating the light-filled gallery with sonorous, resonant hues barely contained in deceptively simple demarcations of space. Four large paintings anchor the whole, orbited by collages and drawings. It's like entering a 3-d version of the artist's brain. Unique relationships emerge between works: a tiny reddish-purple study parked at the bottom corner of a large, predominantly green painting holds both paintings in mutual abeyance, through the vibration of its intense darks. Correspondences and cross-reference circulate the show. Many of the works portray an image-pattern one might associate with a rounded cruciform, insect head or African textile. Their color and placement of material, texture and edge is extremely specific in a way that anticipates image, but the works abstain from recognizable form. They instead harness structure in the service of materials; deckled or cut edges, surfaces of cascading paint and ferocious graphite markings, contained in discrete areas, vacillate rhythmically together, delighting and enrapturing the eye.

Another version of schema re-emerges in Rockwell Kent's Greenland paintings: Greenland People, Dogs and Mountains, c. 1932-35, oil on canvas mounted on panel, 28 1/8 x 48 inches, Bowdoin College Museum of Art, Brunswick, Maine, below. Kent's Greenland paintings are new discoveries, thanks to Steve Martin's art-world yarn, An Object of Beauty. It's interesting to think about how his stylized terrains and Lewczuk's joyous investigations of color and structure approach composition over the seventy year period that divides them.

Elizabeth Conden

Margrit Lewczuk, "Moondog" (2003), fluorescent and phosphorescent acrylic on linen. Courtesy of the artist.

Margrit Lewczuk’s new paintings, the Phosphorescent Paintings that make up this exhibition at the Maier Museum of Art in Lynchburg, Virginia, are a trip into an artistic terra incognito; a realm without signposts or guiding historical precedents, literally, a walk in the dark. The paintings encourage a new way of looking at looking, of seeing the act of seeing. Initially we are presented with Lewczuk’s straight-ahead paintings, most composed from three or four bright or florescent colors, black and white on a dry ground. As in much of Lewczuk’s recent painting, a gridded space and bold graphic design keep the visual readings flat. The presence of distilled figurative forms echoing Aztec sculpture, oriental dancers, or Greek goddesses are a recent development that multiplies the dialectical interpretations this new body of work engenders.

Traditionally, capturing the effects of light and shadow or the emotional and spatial responses of contrasting colors are some of the greatest challenges facing the painter. As modern abstractionists eschewed any reference to the figure or the object, they still relied on the properties of light—reflected light—to convey their expressions. But just as Seurat invented pointillism as a new way of transcribing coloristic light, and Rothko contrasted large planes of saturated tones to enhance the viewers sensitivities to expanses of color, Lewczuk with the Phosphorescent Paintings is likewise investigating the element of light through painting. In this case, with an unconventional technique, paint radiates and generates light itself, rather than merely reflecting it.

"Newman drew the curtains, Rothko pulled down the shades, and Reinhardt turned off the lights." So goes the old but still relevant aphorism about the New York School’s dark drive towards modernistic reduction. In a darkened room, Lewczuk’s paintings radiate unearthly ghost-like effigies of themselves. The eyes require several seconds, perhaps minutes to begin to adjust to this new visual experience. Linear elements stand out like neon. Large areas of glowing phosphorescent matter transmit a sense of depth that is so unexpected, one is forced to question how they’ve conceived of graphic space before. Walking up to a large passage of glowing pigment, I suddenly felt oddly incorporeal, realizing that I, like a vampire gazing in a mirror, could not cast a shadow on this painting. I was struck with a kind of coloristic vertigo. This is not the same kind of refracted light one might experience looking at a stained glass window or a large-scale photo transparency in a light box. In those situations the illumination passes through a colored filter, but Lewczuk’s light quality is similar to the glow of embers in the ashes of a dying fire, or to a swarm of fireflies massed in calculated abstract formations. The paintings seem to function on the backside of the spectrum, forcing me to reevaluate my ideas of how my organs of sense and perception really work.

As an abstract painter, Lewczuk’s investigations of new media are in keeping with the modernist orthodoxy. The sudden appearance of the figure in these, perhaps some of her potentially most abstract paintings, presents another aspect of her practice that requires further contemplation. Are her figures mere compositional devices, a way to introduce curvy seductive organic forms, or is there a deeper, perhaps symbolic, or even spiritual intent? Are they a response to the evanescent qualities of the medium, an attempt to reestablish a classical humanistic content? A statement about the absurdity of the painter’s quest to "boldly go where no man has gone before" and maybe to see what no one has seen before? To not just "see" the light but to "be" the light in a world of darkness? Sometimes, the most interesting qualities a painting can embody are the questions it evokes rather than those it answers, to raise concerns that might evolve into convictions.

CONTRIBUTOR

JAMES KALM has written extensively on the Brooklyn art scene. In 2006 he began posting video reviews of local art exhibitions at his two YouTube channels that have generated over six million views.

Come Together: Surviving Sandy

Margrit Lewczuk and Bill Jensen

Connie’s Drum; Passions According to Andrei

by Alexandra Hammond

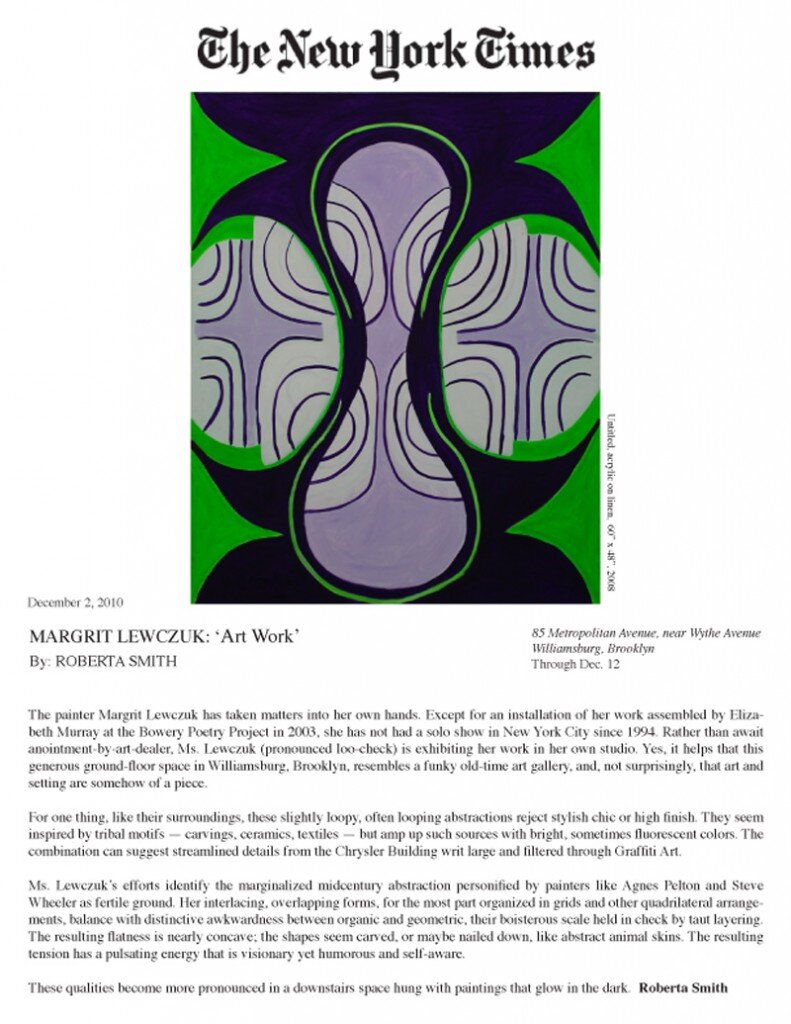

Margrit Lewczuk’s bright paintings titled Connie’s Drum and Green & Purple were installed facing her husband Bill Jensen’s intense diptych Passions According to Andrei (Rublev/Tarkovsky). The adjoining wall was hung with a cluster of eleven of Lewczuk’s smaller paintings, drawings and collages interspersed with eight of Jensen’s brush drawings in black ink. Where Jensen’s work is steeped and somber, Lewczuk’s is fresh and subtlety irreverent. These distinct approaches to abstract painting were created and shown in conversation.

Margrit Lewczuk, “Connie’s Dream,” 2006. Acrylic on linen, 60 x 48″. “Green & Purple,” 2008. Acrylic on linen, 60 x 48″. Courtesy of the artist. Photo by Brian Buckley.

Connie’s Drum and Green & Purple toy with pattern and symmetry but remain unbound by their strict rules. Connie’s Drum in (red, pink, gray, and black) and Green & Purple (in vibrant lime, deep violet and pale lavender) both center on the vertical form of an elongated, rounded hourglass, pushed in at the waist on right and left by ovular forms and supported top and bottom by rounded base and capital, like the silhouette of some hybrid child of an Ionic column and the Venus of Willendorf.

Mexican god’s eyes, the markings of butterfly wings, African waxprints and Ukrainian Easter eggs come to mind. Background and foreground alternate. The viewer can choose whether the concentric, semi-circular lines are in front, and whether or not they connect on this plane of reality or in some paradoxical space within the painting, an infinite space akin to the path of the Celtic knot or the labyrinth. We could see these works as off-the-cuff infographics for mediation, aided by the interaction of color. Lewczuk’s blithe brushstrokes seem to smile into the quantum dimension they make visible.

When I asked Lewczuk about the relationship between her paintings and Jensen’s she said that it could be described as, “same but different.” Their home and studio in Williamsburg feels more like an old Mediterranean or Southern Chinese courtyard house than something one would find near the East River. Both artists’ sensibilities are nested in this place. Both are painters and abstractionists: same, but different.

Bill Jensen, “Passions According to Andrei (Rublev/Tarkovsky),” 2010-11. Oil on linen, 53 1/2 x 78 1/2″. Courtesy of the artist. Photo by Brian Buckley.

Jensen’s studio feels distinctively Old World. Light filters down through metal-framed skylights onto pots and pots of hand-mixed oil paints. Books of ancient Chinese poetry, and Renaissance paintings lie open to key spreads. The study of specific visual modes and strains of thought is apparent, and yet the sketches made from these are turned upside down, remixed and reconfigured by the artist, blending references across centuries. Passions According to Andrei (Rublev/Tarkovsky) is no exception.

The diptych is comprised of a mostly white canvas at right centered vertically against a slightly larger densely-colored canvas at left. In the case of Passions, whiteness does not equate with lightness. The weight and solidity of the right-hand section is undeniable. Layers of primer have been troweled on, sanded down, the process repeated. It’s like the wall of an ancient building, smooth and gently mottled with the patina of ware. Floating in the center left of the composition are mirrored shapes, more sculpted in low relief than rendered on the surface. The lower form bleeds off to the next canvas and turns to shadow there. The forms are mysteriously organic: falling angels, heavy grazing animals looking at their reflection, the gnarled shells of fossilized sea creatures. The adjoining canvas throws us into a coexistent dimension, roiling and intense in deepest violet with moments of ochre and burnt sienna. There is something of the rapture of El Greco’s skies here, a deep spiritualism that is offbeat, personal and esoteric.

The work’s title refers to the 1966 film The Passion According to Andrei by Russian director Andrei Tarkovsky, an interpretation of the life of Medieval icon painter Andrei Rublev. Jensen derived the mirrored, floating shapes, which appear in this piece and others, from Rublev’s icon of The Trinity. The film traces Rublev’s loss of faith, and its recovery through the witness of another artist’s miraculous creation. The juxtaposition of two canvases in Jensen’s piece speaks of what he calls a “fracture in time and space,” but perhaps it is also a strategy for conveying life’s deep sorrow and its opportunities for redemption.

Encountering Lewczuk and Jensen’s work, one feels a renewed sense of the relevance of abstract painting, and also, perhaps, that abstraction is the wrong term for a way of making pictures that are not figural, yet are rooted in the specifics of place and human emotion. This is a different meaning for relational aesthetics, an aesthetics built up over decades of relating. The works offer two perspectives on a co-existence: same, but different.